How One Principal Built Her Leadership Team to Improve Instruction

Amanda Graham

Principal, St. Pauls Elementary, Robeson County, North Carolina

This profile is part of the Follow the Leaders project, an ongoing series from Relay Graduate School of Education to share insights and inspiration on leading for equity, wellness, and achievement. Subscribe here.

Like other schools in Robeson County, North Carolina, St. Pauls Elementary School struggled with low student performance, with improvement efforts stagnating following the pandemic. After becoming the school’s new principal in Fall 2021, Amanda Graham aimed to strengthen teacher practice before a new high-quality curriculum was introduced districtwide. To do so, she recognized she needed to grow professionally herself, and move beyond her past practice as “the sticky note queen:”

“[After observing a teacher’s classroom] I was really good about leaving a nice little note on [their] laptop or desk, but I wasn’t really coaching, pushing, or growing teachers to best help students,” she says.

As part of a districtwide initiative to improve student outcomes by shifting adult culture and practice, Graham and other principals in the Public Schools of Robeson County (PSRC) participated in intensive coaching through a partnership between Relay Graduate School of Education and the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s Office of District and Regional Support. Building off of instructional practices in Relay’s Leadership Programs and supported by one-on-one coaching, Graham began spending as much as 85 percent of her day in classrooms, observing instruction.

The following year, St. Pauls Elementary received the designation of “exceeded growth” - part of the North Carolina system for tracking school accountability - for the first time since 2016. Students at the school posted double digit gains in math proficiency at all tested levels and nearly 10 percent gains in English. In 2022-23, St. Pauls Elementary’s scores leveled out after the previous year’s growth, while Graham began coaching three other elementary schools which either met or exceeded growth and improved proficiency in all tested areas.

Building out the Instructional Leadership Team

One of the focus areas of her Relay training was on how to build her instructional leadership team (ILT). As principal in a new building, Graham recognized that all leaders could strengthen their coaching skills and that she could distribute leadership among her team, which included the school’s assistant principal and academic coach.

“I needed to let them know that an ILT means we’re working as one to improve the instruction on our campus for all of our students, because if we’re not unified, then we’re just doing random things.”

Here’s how Graham built the coaching capacity of her leadership team:

1. Strengthening her own skills as an instructional leader

Graham realized that in order to model effective leadership practices for her ILT, she had to strengthen her own skills. “I needed to get better in order for other leaders to get better,” she says.

During regular in-person and virtual meetings, Relay coach Jeanine Zitta worked with Graham on delivering real-time feedback, using the “Get Better Faster" sequence of action steps to coach teachers on the highest-leverage practices to shift instruction and, Graham says, “breaking down walls with my own fears of practicing live.”

“I didn’t realize how hungry I was for help,” Graham says. “All I knew was my way, or if there was some PD that was forced down our throats, we’d sit through it and check a box and say that we did it.”

Over time, Zitta says, Graham developed confidence to build on the Get Better Faster coaching strategies and adapt them to meet the needs of her teachers and ILT members. “She understood [what parts of the] protocol were necessary, and what can be adapted based on who you’re coaching or what data you’re looking at,” Zitta says.

2. Setting a vision for the instructional leadership team

Before the school year began, Graham brought her leadership team together and shared the goal for the year: preparing teachers to deliver the new curriculum. She also imparted a common message to convey to teachers:

“We’re going to do a core curriculum this year because our kids deserve it, and we’re going to do it in every grade level—and we’re going to do it with you. We’re going to plan with you. We’re going to coach beside you. We’re going to walk into your room with the lesson in hand, and we’re going to become a second teacher in that room.”

3. Aligning time, tools, and talent to build instructional leadership team capacity

Graham developed calendars that ensured that she and other ILT members would be in classrooms or instructionally focused meetings more than 80 percent of the time. (For examples, see Relay’s Academic Rigor for All: Leveraging a Playbook to Move Every Student to Mastery.)

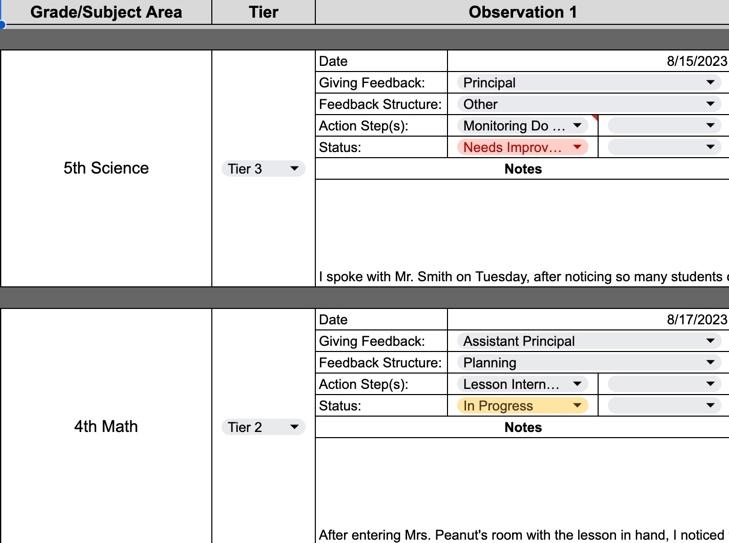

To ensure that ILT members developed a common understanding of schoolwide instructional priorities, Graham created a teacher action step tracker. The tracker, which was refined during Zitta’s ongoing coaching, provided a single place for all team members to record their classroom observations and action steps for teachers. Color-coded status indicators helped Graham identify gaps in coaching led by other ILT members so she could target support. She explains:

“If something’s staying in the red, you can quickly see where they’re not fixing an action step. It tells you what conversations you need to have with your leadership team—are you coaching? Have you gone in and shown the teacher a model? What else have you done?”

To support coaching by other ILT members, Graham leaned heavily into using her time in classrooms to model and coach them, taking into account their individual strengths. She explains:

“I leaned into their comfort zones. [One] did better watching me model first and then wanted me to stay in the room for the second time, but I was intentionally in the back with my mouth shut, and I wouldn’t intervene unless things went way off, so on the third round, I could be out of the room.”

Zitta says this investment in time and capacity building proved transformational for the ILT:

“One of the best things she did was model everything for her team. She made sure the team was comfortable before they did the work, and was mindful about how they felt about doing it themselves so it would be done well, with integrity.”

4. Developing structures to calibrate the team

In order to develop a common understanding of how to coach and support teachers, Graham worked with her coach to focus instructional leadership team meeting agendas on using the “See it/Name it/Do it” protocol to develop data-informed, shared action steps. During the meetings, the ILT works together to identify areas of growth and discuss potential action steps such as targeted observation and feedback or “practice clinics” targeting specific high-leverage instructional practices. They then agree on which action step is the most important to pursue as a team. “Whatever that step looks like, we make it together, and then we practice it,” Graham says.

Regular calibration walks also helped norm observations and action steps for ILT members. During these walks, the ILT visits classrooms together without discussion until they return to their meeting room. Graham then solicits feedback from each team member, writing their observations down on chart paper so the team can see each other’s observations. Doing so had a two-fold benefit, Graham says:

“It helped me see what their lens was when they’re in the classroom. But after the third or fourth thing that was shared, we could see that our language was starting to sound the same. That helped them see just how fast it was for us to find a gap on our campus that we can address right now as a team. It keeps us focused on the right things at the right time.”

Instructional Leadership Districtwide

At first, a unified ILT allowed Graham to address a principal’s many other tasks, knowing that her team members had a common vision and understanding of needed instructional action steps. But the true test of capacity building came during the 2023-24 school year, when she became a district principal coach and her AP was named St. Pauls Elementary’s principal, in large part because of the team’s work.

Working with Relay coaches, Graham now supports the district’s 36 principals, focusing on strengthening their own instructional leadership teams. She says, “Principals may have set time for ILT meetings, but they may not know how to use it. They will benefit from concrete tools and protocols, and that will be 36 schools all in the same unified work.”

Selected to join the 2023-24 cohort of Relay’s Leverage Leadership Institute Fellowship, Graham will continue to receive coaching and other support in her district leadership role. But, she says,

“I’m proudest of what I left—my leadership team. A one-man ship is not a ship that anyone wants to sail. So, why not surround yourself with people that have the same vision that you do, or that can be molded to have the same vision that you do, because they are invested in students and education?”

Taking it Back to Your School

- What is the purpose of your instructional leadership team?

- Do you have a weekly schedule that allows enough time for classroom observations, debriefs, and planning?

- What 2-3 next steps might you take to better leverage your time together to ensure it strengthens the quality of teaching and learning?

Amanda Graham currently serves as the “Relay Coach” Principal Supervisor for Public Schools of Robeson County (PSRC). She has worked for the district since 2002. During her career with PSRC, she has served as a classroom teacher, a curriculum specialist, an assistant principal, and as a principal for seven years. She has received coaching from Relay for the past three years. She is the mother of a 13-year-old son and two stepsons. When not working, she enjoys camping and fishing with her family.

Subscribe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter for more expert insights from school and system leaders.