(Re)Focused on Learning: Leading a Shift in Teacher Coaching to Deepen Student Understanding

Carice Sanchez

Chief Academic Officer and Co-Founder, Henderson Collegiate, Henderson, N.C.

Executive Summary

The chief academic officer of a high-performing K–12 public charter network in rural North Carolina leads a pivotal shift in instructional leadership—moving from a focus on teacher moves to a sharper lens on student understanding as the driver of real-time adjustments in teaching. With tools and practices from Relay GSE, she:

- Prioritized real-time monitoring and response to student learning as the network’s core strategy for deepening student understanding;

- Extensively practiced and refined instructional coaching on this strategy with her core leadership team before rolling it out to teachers;

- Ensured every teacher was coached by someone with deep content expertise by enlisting expert teachers as coaches; and

- Targeted coaching to classrooms where the strategy would most accelerate student learning and teacher growth, shifting focus as educators built skill.

As a result, leaders report teachers are internalizing learning goals more deeply, responding more nimbly to student misconceptions, and improving both the pace and depth of student learning.

The Needle Wasn’t Moving

Carice Sanchez had plenty to feel good about. Fifteen years after co-founding Henderson Collegiate with a single grade in a modular classroom, the school had grown into a high-performing K–12 network with a new campus, an impressive college acceptance rate, and some of the strongest results in the state. Yet progress had plateaued—short of what she fervently believed the schools and their students could achieve.

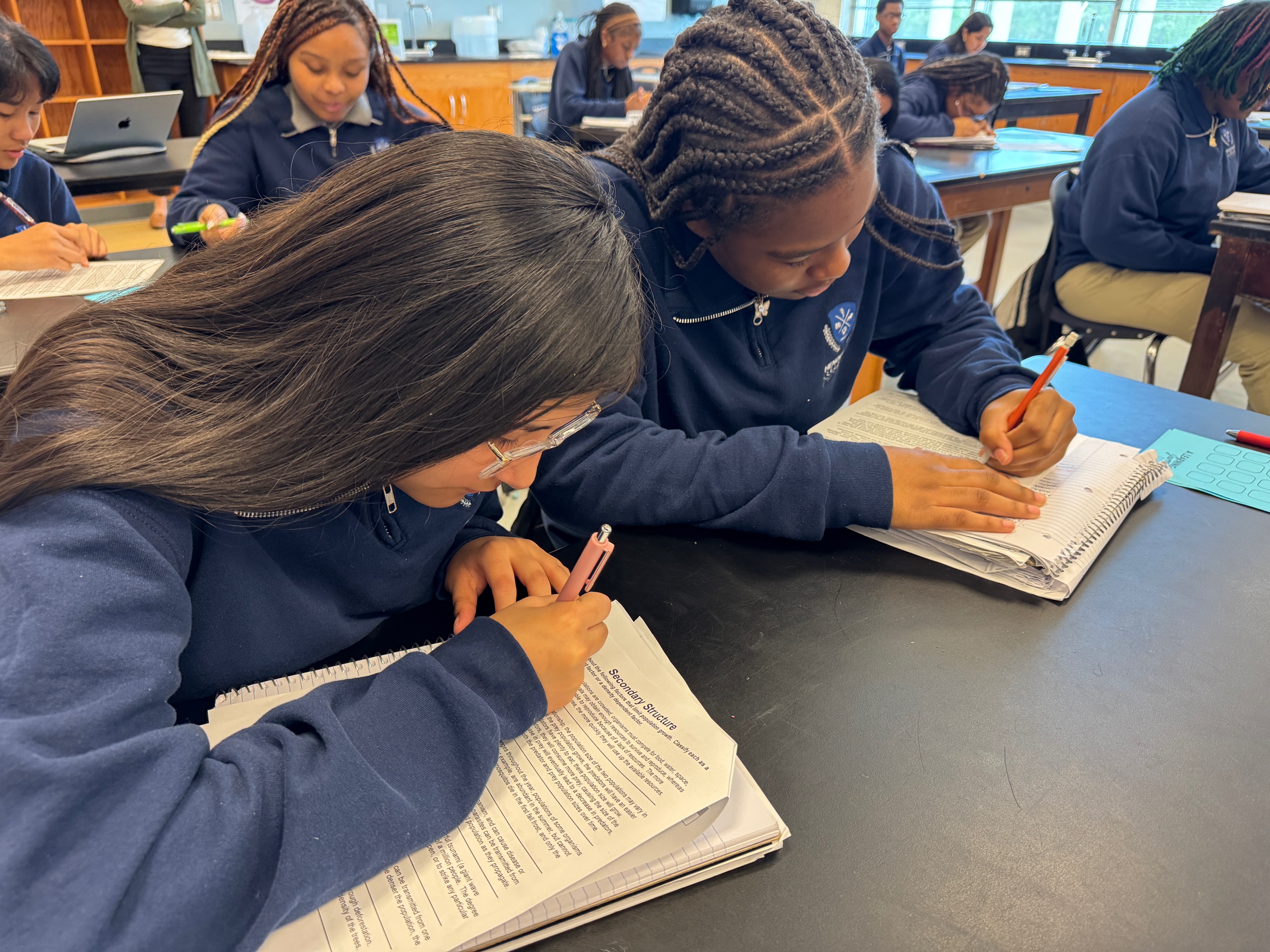

The primary challenge was clear: Students could give the right answers, but their notebooks and discussions often revealed a shaky grasp of the underlying ideas. “They could say the word photosynthesis,” Sanchez said. “They could maybe even define it, but they couldn't apply it in a different context.”

To honor the school’s promise to get first-generation college students not just into college, but to succeed there, her team needed to zero in on student thinking.“We were proud of the work,” said Sanchez. “But the needle wasn’t moving the way it had been. We needed to push in a new way.”

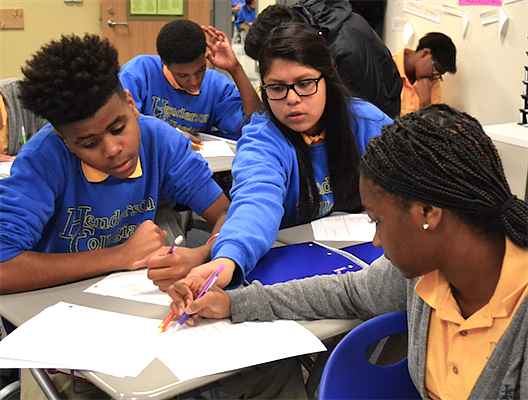

That push sparked a network-wide shift in focus: away from teacher actions and student activity, and toward student thinking. Leaders recognized the clearest window into student understanding comes in the moment—while students are working, discussing, and applying new concepts. Real-time checks let teachers spot confusion as it emerges and respond immediately to deepen understanding.

To make that happen, leaders refocused the network’s established culture of feedback, planning, and coaching on a new instructional goal: helping teachers monitor and respond to student understanding in the moment. Existing systems—like regular classroom observations and collaborative planning—became vehicles for building this skill across the network.

Turning on Light Bulbs

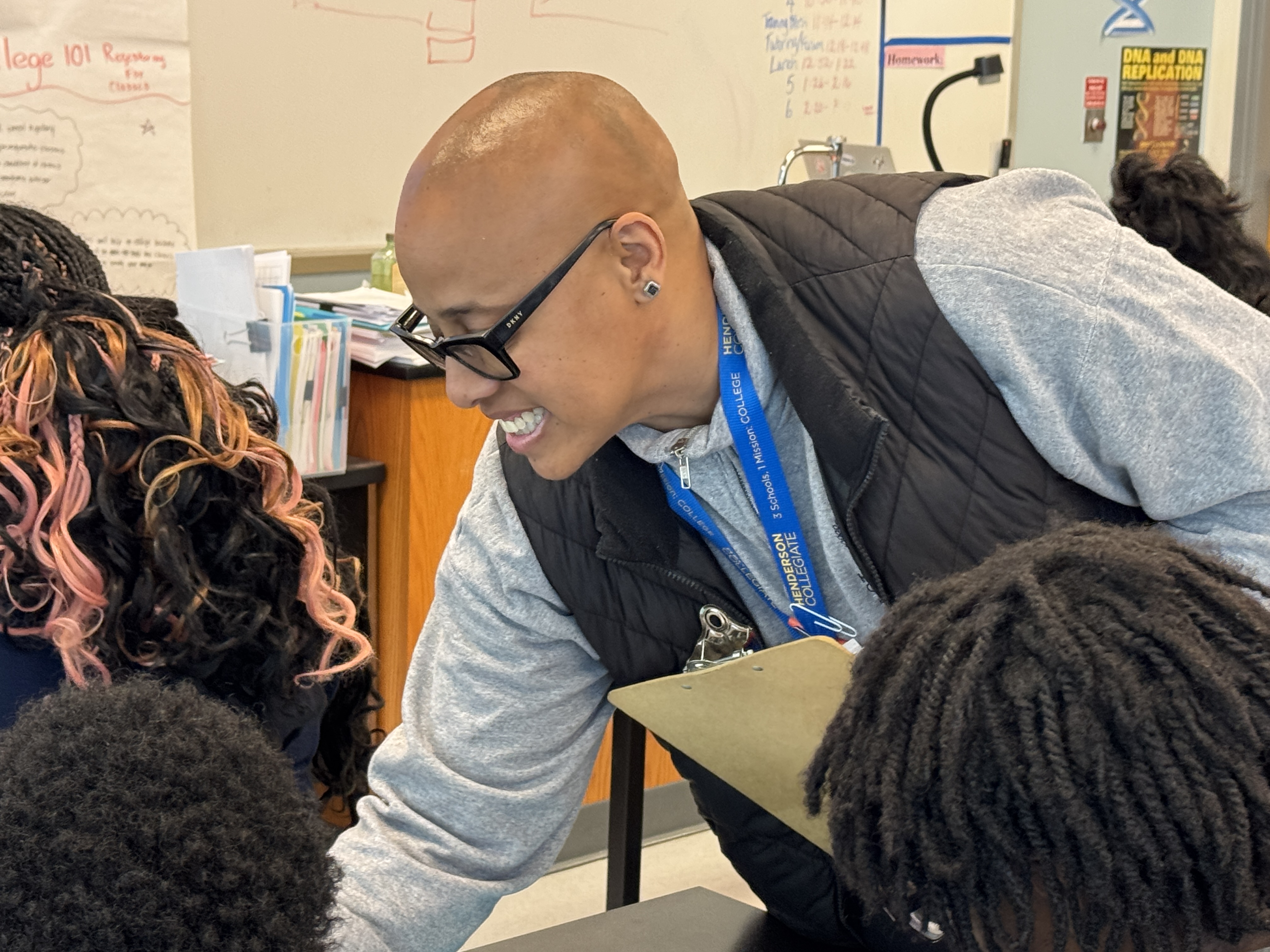

The shifts in both teaching and teacher coaching are clear in a recent 9th grade biology lesson. Sanchez observes as High School Principal Taro Shigenobu, a former middle school science teacher himself, coaches teacher Jaimi Semper through a unit on genetics. From their planning that morning, the two leaders are focused on ensuring students fully grasp that environmental factors can affect gene expression without altering DNA–a concept called “epigenetics.”

Throughout the lesson, Sanchez keeps her eyes and ears on Shigenobu as he makes repeated laps through the room—glancing at students’ notebooks, listening to partner talk, and conferring with Semper about what she’s seeing and how to respond. After each lap, he huddles with Sanchez at the back of the room on how to move forward.

At one point, Sanchez gives Shigenobu the go-ahead to step in and address lingering confusion. With a raised hand, he pauses the class and prompts students to reason—first with their partners, then with the whole group—how epigenetics could explain why a clone might not look like its original. He then drives home the point by flicking the lights on and off. “The gene stays the same,” he says, “but the environment turns on or off how it’s expressed.”

As students return to their partner work, the three adults confer quietly at the back of the room. At Shigenobu’s invitation, Semper recounts what he did and how it helped deepen student understanding—reinforcing the teacher’s sense of when and how to make the move herself. Sanchez praises her insight, then offers Shigenobu her own feedback: next time, step in sooner. (For a more detailed description of this example).

She explains: the first priority is resolving the students' confusion—but when that requires a coach to step in and model, it must also support teacher growth. “It’s okay if the coach steps in,” Sanchez says. “But only if we make sure the teacher learns from it. Otherwise, we’re not helping the teacher grow.”

The HC Way

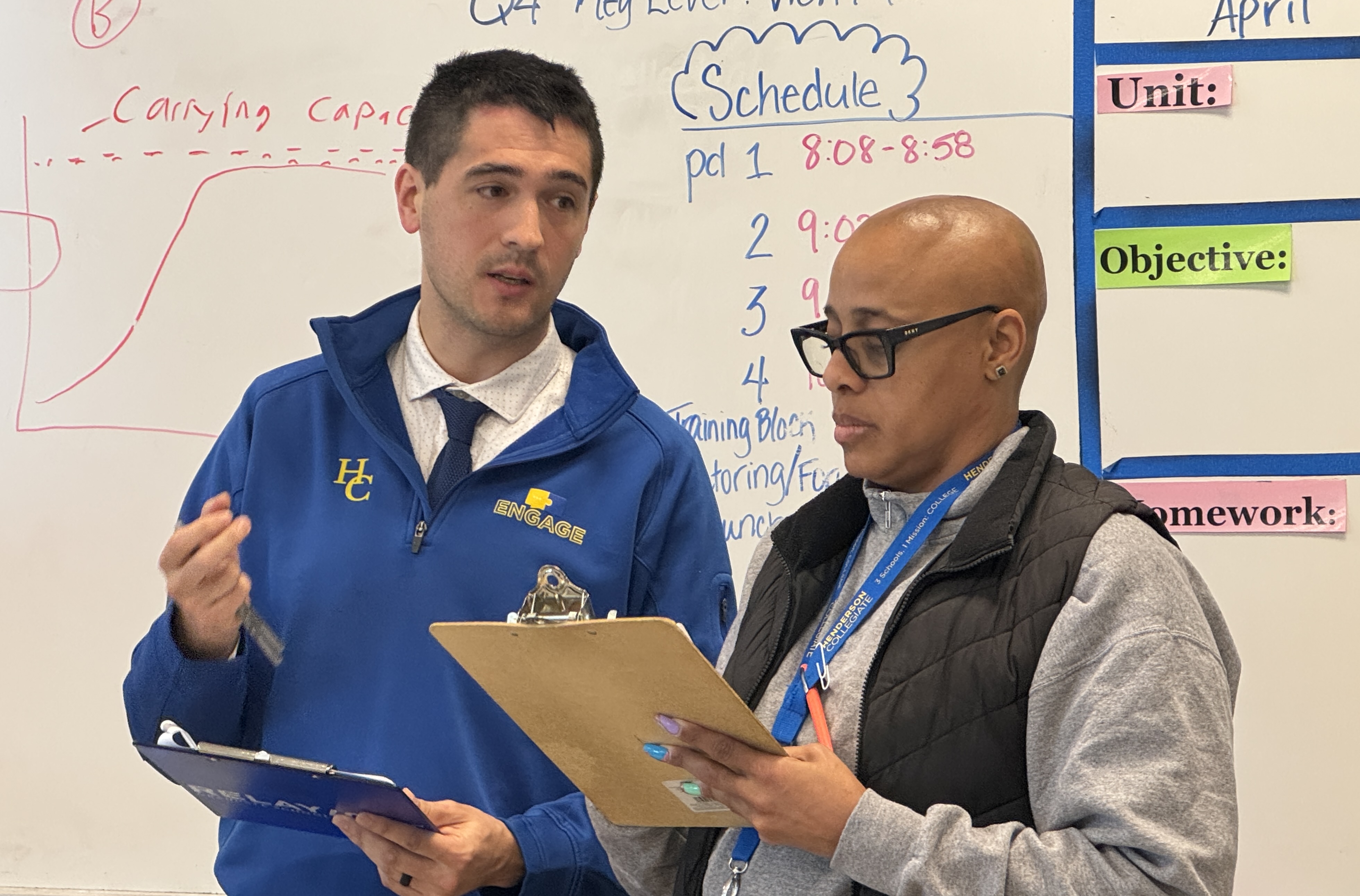

The clarity and coordination on display in the biology classroom didn’t happen overnight at Henderson College. It emerged through a purposeful, months-long rollout of practice, refinement, and scaling—what Sanchez and her team call “The HC Way” of implementing new strategies.

After first learning about “monitoring the learning” from a Relay training, Sanchez practiced the strategy herself. She used Relay protocols to analyze lesson plans, identify the most challenging concepts, and plan how to look and listen for—and respond to— evidence of student understanding; She also determined how to coach the teacher to do the same.

The network leader then trained her top six instructional leaders: the principals of Henderson Collegiate’s elementary, middle, and high schools, and each of their directors of curriculum and instruction. “We had to become really good at it first before we rolled it out,” she explains. “So we practiced, we spent about a month practicing it, videoing it, giving one another feedback. Once we had a handle on what we were trying to execute, then each principal and their DCI trained their instructional coaches on it.”

Only then did they begin coaching teachers on the practice—with Sanchez supporting her principals on their coaching of their coaches.

Meanwhile, she ensured structures were in place to support the work. Coaching teachers to deepen students’ conceptual understanding, she explains, only works if the coach has sufficient subject-matter knowledge to identify the most critical concepts—those that advance learning the furthest and likely to trip students up. By elevating a group of the network’s most expert teachers as coaches, Henderson Collegiate ensures every teacher is coached by someone with the right expertise.

Not all teachers would get coached in the practice at the same time. Each schools’ leaders targeted classrooms they believed had the greatest potential to benefit—both in student learning and teacher development. At the end of each quarter, they reassessed where to focus.

They see themselves getting better

Sanchez and her team emphasized that the network was ready to take on the practice. Classroom management and routines were well established. Curriculum adoption and strong lesson planning meant students were engaged with grade-level content worthy of their college aspirations.

Just as important, a culture of continuous improvement—grounded in frequent observation and feedback—was already deeply embedded. “They see themselves getting better and our teachers love feedback,” says Sanchez: “And so there wasn't much change management around the culture of teaching because that's just what we do.”

Network leaders report consistent evidence of deeper understanding of key concepts in student work and in their classroom discourse. And at the end of each quarter, the classrooms prioritized for the coaching have had enough progress to no longer require the intensive support.

Preliminary data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction also is encouraging. Network-wide, the percentage of students scoring proficient (at least a level 3) on state assessments grew from 72% to 80% from 2024 to 2025 in English Language Arts, and from 83% to 87% in Math.

Shigenobu says he’s not surprised by the gains. “What I've seen so far is pretty much any student gap we've been able to close,” says the high school principal. “It develops the teacher, the students, and then the leader, because all three are getting action steps.”

Taking it Back to Your School

Sanchez and her team recognized the need to shift their focus from teacher moves to student understanding after closely examining student work and listening to classroom discourse. How clear a window do you have into student thinking across classrooms? How could you capture a more complete picture?

To roll out the new practice, Sanchez followed a deliberate, staged process: first building her own expertise, then developing that of her top instructional leaders, and training their instructional coaches. How does this approach compare to how new tools or practices are introduced in your school? What elements of “The HC Way” could you incorporate moving forward?

Sanchez notes that Henderson Collegiate was ready to take on a new practice like monitoring and responding to student understanding in real time. Strong classroom cultures were in place, students were engaged with grade-level content and tasks, and teachers embraced frequent feedback.

Which of those conditions exist in your school—and which don’t? Where might it make the most sense to focus first to help your school reach the next level?

At Henderson Collegiate, all teachers are coached by someone with deep expertise in their subject matter. To ensure this, the school elevates a cadre of expert teachers to serve as part-time coaches. To what extent are teachers in your school coached by someone with that level of expertise? What opportunities exist to strengthen instructional coaching at your school?

Artifacts

Subscribe

Sign up for our monthly newsletter for more expert insights from school and system leaders.